Long famed for high quality Aberdeen-Angus cattle, the North East contains a quarter of Scotland’s arable land and consequently farming is an essential feature of rural life.

The Agricultural Heritage Trail is a guided trail which focuses on farming life in the North East of Scotland. The trail ties in a visit to Hareshowe Farm and is marked with Corten steel posts incorporating images from the James Morrison Photographic Collection. Morrison’s work provides a remarkable record of daily life in rural Aberdeenshire and these prints are taken from a group of over 600 glass plate negatives created between 1890 and 1915.

The Agricultural Heritage Trail has been designed to provide an intriguing insight into rural farming life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At each feature you will find an interpretation panel, coupled with QR codes for further reading.

If you want to follow the trail you can either download the “Trails at Aden Country Park” leaflet or visit the park and pick up a leaflet from either the Aberdeenshire Farming Museum, the Aden Craft & Gift Shop, or the Visitor Information Centre. Please be aware the downloadable leaflet is 32MB in size.

James Morrison Photographic Collection

The Agricultural Heritage Trail is comprised of photographic and text which relate to the James Morrison Photographic Collection. These prints are taken from a group of over 600 glass plate negatives created by photographer James Morrison between 1890 and 1915. Morrison’s work provides a remarkable record of daily life in rural Aberdeenshire.

Born on 31 August 1865 at Langlums near Methlick, Morrison grew up helping his father on the farm at Newseat of Shivas and later at Stoneyards, Balmedie. He married Helen Riddel in 1911 and supported his family of three children through the mending and manufacturing of bicycles at Menie, Belhelvie. Photography was a pursuit of his bachelor days and he used a converted scullery as a darkroom at Stoneyards.

Morrison travelled the Aberdeenshire countryside on his bicycle with a three-legged camera and boxes of glass plate negatives. Although an amateur, he possessed a high degree of skill in both his technical competence and composition.

His images capture the rapidly changing nature of agricultural work in the early 20th century. By the time he developed his final exposure, working horses, feeing markets, bothies and their ballads were becoming part of a bygone era. The arrival of mechanisation in the form of North American binders and domestically produced reapers brought an end to the dominance of animal-led farming methods and radically changed the social fabric of the countryside.

Images courtesy of Aberdeenshire Council Farming Museum and The Buchan Heritage Society.

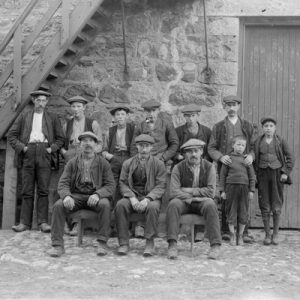

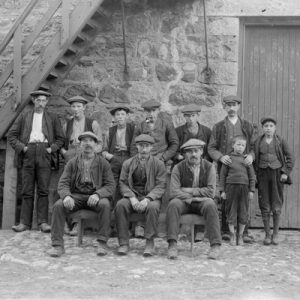

1 A Busy Working Day

In this image, farm workers pose with two kitchen servants outside a steading building. One is polishing a peaked collar while others hold various bits of harness. The man on the left with the dog is probably the grieve.

In this image, farm workers pose with two kitchen servants outside a steading building. One is polishing a peaked collar while others hold various bits of harness. The man on the left with the dog is probably the grieve.

At the age of 13, a young loon might start work as a Coo bailie or an Orraman, and two or three years later become a Plooman or a Horseman with a pair of horse.

The long hours spent each day with the horse team created strong bonds. As well as caring for their horses’ health, the horseman lavished time and attention on the cleaning and maintenance of harness. Special events such as the local ploughing match or church picnic provided the opportunity to show decorated harness.

2 Land Management

Two forresters pause before felling a tree which has been ringed with axes. A Canadian cross cut saw stands ready to complete the job. Before land could be used for farming, it first had to be cleared of unwanted elements such as trees, undergrowth, and rock. Stones would be prised out of the ground using a crowbar and tramp pick and levered onto a paddock of sledge. Broom was uprooted in the jaws of the breemdog or cut back with shears. In mossy areas, heather was removed by a flauchter or turf spade and the land then fertilised by muck and lime, or by seaweed on coastal sites. Trees also had to be removed, with the cut wood carted away for further use as timber.

Two forresters pause before felling a tree which has been ringed with axes. A Canadian cross cut saw stands ready to complete the job. Before land could be used for farming, it first had to be cleared of unwanted elements such as trees, undergrowth, and rock. Stones would be prised out of the ground using a crowbar and tramp pick and levered onto a paddock of sledge. Broom was uprooted in the jaws of the breemdog or cut back with shears. In mossy areas, heather was removed by a flauchter or turf spade and the land then fertilised by muck and lime, or by seaweed on coastal sites. Trees also had to be removed, with the cut wood carted away for further use as timber.

3 Ploughing the Way

A farmer and his team of horses use a single-furrow swing plough to turn over the soil after a previous harvest. Ploughs have been in use in Scotland for over 5,000 years. Early ploughs were made entirely of wood, and by the 1700s wood ploughs included a few iron elements to improve durability. You can see one of these early wooden ploughs at the Aberdeenshire Farming Museum.

By the mid-1800s, metal ploughs were being mass-produced by foundries and more locally by blacksmiths. Horse ploughs continued in use until after the Second World War and were eventually replaced by tractor ploughs.

4 Harvest Season

A blinkered horse pulls a Princess Reaper manufactured by McDonald Brothers, Portsoy. The hay, after having been cut, would be bound by hand. This type of implement was in common use by crofters and small farmers until the end of the World War II.

Mechanised reaping was not practised on large farms until the 1850s after clay drainage had flattened the surface of the fields. Grain cut with a reaper still had to be hand-bound into a sheaf, and it took until the 1890s for self-binders to reach inland Aberdeenshire.

5 New Field Technology

Three horses pull a New Ideal Deering Binder: an innovative and complete piece of machinery that delivered the bound sheaves to the right of the equipment out of the pathway of the next cut.

However, the almost magical knotting mechanism broke down from time to time, and then no doubt the horseman looked enviously at the croft tenant still working with old ways with a scythe or reaper.

6 Hard Work at Hairst Time

Grieve Charlie Philip (left) poses with his men in front of the corn ricks at Leyton Farm, Belhelvie. After grain had been harvested, the bound sheaves had to be carted from the field to the farmyard for storage as a stack, or rick.

Grain was usually cut green and so the cut sheaves were left to ripen in stooks (a group of sheaves of grain stood on end in a field).

At the farm, the sheaves were laid on the rick foons (the foundations of the stack, made of stone, a wooden platform, or a raised iron latticework) in a clockwise direction. Each layer of sheaves sloped downwards from the centre to prevent the entry of rainwater. Finally, the completed rick was thatched with sprots or rushes and secured by straw ropes.

7 From Here To There

In this rare glimpse of rural transportation, two oxen pull a family in an extremely primitive cart made up of various scavenged bits and pieces including machinery pulleys for wheels.

Relying on animal power and precarious vehicles, poor road conditions often prevented travellers from reaching their destination. Roads were notoriously bad, often nothing more than a muddy path. In the 1800s it took a coach 4 hours to travel from Newburgh to Aberdeen, now a 20 minute car journey.

8 Milking Time

A kitchie deem (kitchen dame or maid) milks an Ayrshire Cow assisted by supporting players in this posed photograph.

Dariying has long provided an important source of food and income to rural residents. Many farms had a dairy room as part of its operation, usually located in a cool shaded spot, where fresh milk was placed into churns to make butter or used to make cheese.

The dairy required easily cleaned surfaces, usually made of stone, and good ventilation. Women often undertook this process, completing all tasks from milking the cow to selling the food products.

9 A Family Affair

Men and women of all ages worked on the farm. As seen in this posed photograph, the two young boys on the right are probably standing with their father, whom they would have helped with his tasks about the farm.

The Aden Estate was busy and productive during its heyday in the early 20th century. Most of the Estate was composed of more than 50 tenant farmers, who paid rent twice yearly to the estate factor.

The ‘Big House’ included at least 7 servants, and the home farm, with its horseman, gardener, gamekeeper, and hired farm labourers meant this was a hive of daily activity. The working day was often hard and long. For example, farm workers at this time were expected to be able to carry 127 kg sacks up stairs such as those at the left of the photo, often without the luxury of a hand railing.

Download Agricultural Heritage Trail Leaflet

To download a copy of the Agricultural Heritage Trail leaflet please click on the Download button below. Alternatively you can pick up an Agricultural Heritage Trail leaflet from the Visitor Information Centre or the Aberdeenshire Farming Museum.

In this image, farm workers pose with two kitchen servants outside a steading building. One is polishing a peaked collar while others hold various bits of harness. The man on the left with the dog is probably the grieve.

In this image, farm workers pose with two kitchen servants outside a steading building. One is polishing a peaked collar while others hold various bits of harness. The man on the left with the dog is probably the grieve. Two forresters pause before felling a tree which has been ringed with axes. A Canadian cross cut saw stands ready to complete the job. Before land could be used for farming, it first had to be cleared of unwanted elements such as trees, undergrowth, and rock. Stones would be prised out of the ground using a crowbar and tramp pick and levered onto a paddock of sledge. Broom was uprooted in the jaws of the breemdog or cut back with shears. In mossy areas, heather was removed by a flauchter or turf spade and the land then fertilised by muck and lime, or by seaweed on coastal sites. Trees also had to be removed, with the cut wood carted away for further use as timber.

Two forresters pause before felling a tree which has been ringed with axes. A Canadian cross cut saw stands ready to complete the job. Before land could be used for farming, it first had to be cleared of unwanted elements such as trees, undergrowth, and rock. Stones would be prised out of the ground using a crowbar and tramp pick and levered onto a paddock of sledge. Broom was uprooted in the jaws of the breemdog or cut back with shears. In mossy areas, heather was removed by a flauchter or turf spade and the land then fertilised by muck and lime, or by seaweed on coastal sites. Trees also had to be removed, with the cut wood carted away for further use as timber.